Although I wasn't expecting a full house of newspaper readers, the picture painted in that classroom was worse than anticipated.

There may have been only 25 students in the class, but they were mid-career professionals in their late 20s upwards, and so not necessarily from the savvy young Web generation.

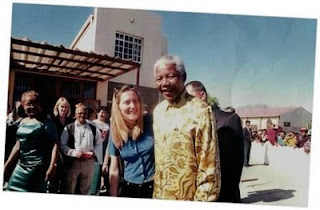

For the past six months, I have been engaging with journalists from around the globe about our craft. I have met an incredible bunch of passionate people – from the Nieman fellows and affiliates to visiting journalists such as the New York Times’s David Rohde and the New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson (pictured below left). I have been inspired and uplifted by the high standards and quality of reporting around the globe.

But during our special time together, it has been hard not to talk about the elephant in the room - the crisis in newspapers and the doom and gloom in the industry. At times it has been depressing. At others, painful. Such as when a colleague bluntly told a seminar recently that: “The epitaph has been written… newspapers are dead.”

But what does it mean when we talk about the crisis in the print industry? And why is the public debate centred around the loss of newspapers per se?

As US media columnist Clary Shirky puts it, society doesn’t need newspapers. It needs journalism.

So, shouldn’t we be talking instead about journalism, of the importance of saving quality reporting, of making sure we are still out there where the action is? Shouldn’t we be talking about the struggle to keep the craft of reporting alive amid the technological revolution that is rapidly changing the way the world communicates?

"85% of online content is generated from newspapers"

The newsgathering process is unpredictable, messy and costly. There are no guarantees. Reporting is like fishing. If you don’t cast your rod, you have absolutely no chance of catching a fish. First-hand accounts are paramount.

It is about being there, on the ground, doorstopping people, hounding them at odd hours, hanging out and waiting. It is not about sitting at your computer waiting for a press release to land in your inbox.

And if newsrooms become so stretched that they stop sending out reporters to cover news, then the web will not be getting much news either. Why is this so? Because most of the news on the web is aggregated content. And where does most of this aggregated news come from? Struggling newspaper newsrooms.

Former Los Angeles Times editor John Carroll estimated in 2007 that "roughly 85 percent of the original reporting that gets done in America gets done by newspapers. ... They're the people who are going out and knocking on doors and rummaging through records and covering events and so on. And most of the other media that provide news to people are really recycling news that's gathered by newspapers."*

Increasingly newsrooms are transforming and catering to both mediums - the Web and newspapers, but the point remains: there is a heavy dependence on traditional newsrooms. It is these newsrooms - the engine rooms of news - which need to be protected and boosted. Newspapers and the Web both need solid newsrooms.

If a newsroom is forced to cut back so much they don’t have reporters covering key beats, it is a loss to society. If a reporter is not given the chance to spend time on an investigative story, then we are going to lose our vital place as the muckrakers of society, keeping the rich, powerful and influential on their toes.

And if we start to let other people compile the news for us - ie politicians, publicists or Public relations officers - then we are not doing our jobs properly and society is at risk.Let's fact it. News that lands in a reporter's inbox is usually some form of spin.

And if we allow a culture to develop in which managers become so risk-averse that they don't send teams out unless they are absolutely sure they are going to return with a story, then we are on a road to nowhere.

There is a lot to be excited about in this media revolution. Blogging and twittering have opened up new avenues for citizen journalism and first-hand, on-the-ground reporting. But newsrooms should not go out on a wing and a prayer in the hope that a blogger will do their work for them. They still need to be there, out in the field. They are the professionals, they have the expertise.

Last week during a seminar presented by Columbia Journalism School professor Sree Sreenivasan, a name was thrown around the room for the emerging journalist of today: a "tra-digital journalist" (coined by Sig Gissler, administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes). This is a journalist who retains the traditional, good old-fashioned values of the craft but who has the right attitude to be able to adapt to the changing technology.

Sounds good to me.

* Caroll source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/newswar/tags/newsgathering.html